AGING WITH HIV text by Nicola Scevola

Stephen Helmke always wanted to be a physician but when he was in medical school in 1985 he discovered he was HIV positive and assumed he would never survive enough to finish his studies. He left the school in Louisiana and moved to New York. “When the antiretroviral therapy became widely available I was finally able to focus on my future again”, says Helmke, who’s now 49. “I wanted to go back to medical school but it was too late”. Today he works as sonographer at New York Presbyterian Hospital, conducting ultrasound examinations to help physicians specialized in geriatric cardiac diseases. In the US there are many HIV patients like Helmke who started following an antiretroviral therapy, reacted well to the treatment and are now conducting a fairly normal life. In fact half of the HIV/AIDS population in the United States will be 50 or older by 2015.

In the Nineties, a typical Act Up meeting in New York attracted a huge crowd of people aged 20 to 25. Nowadays participants are fewer and mostly over 45. But this pivotal development is bringing new challenges to the treatment and prevention of the disease. Today most physicians call HIV a chronic, manageable disease but few among them mention the problems that an aging HIV population is starting to show. Helmke, an ACT UP member himself, used to be able to take a pill-holyday every year for a month. Now he can only stop for a day before his condition starts to deteriorate. HIV finds hiding places in the body out of the drugs’ reach. Once medication is halted, these sleeper cells send out armies of new viral invaders to resume the war. So the current thinking is that the drug regimens are lifelong commitments. “Death used to be the biggest threat for HIV patients, today the biggest problem is accelerated aging”, says Helmke. “My system is worn down by polypharmacy”.

As long-term antiretroviral therapy escorts significant segments of the American HIV population into old age, there’s now the opportunity to focus on the late effects of the treatment. “At the height of the plague, gay men used to say: use a condom or die. Now they say: use a condom or take a pill”, says David France, author of How to Survive a Plague, an Academy Award nominated documentary. “But nobody exactly knows what are the side effects in the long run”.

The United States has been stable at about 50,000 new infections a year for the last decade but research shows that older people with HIV are more likely to develop cancer, liver and kidney disease, as well as depression. They are likely to suffer from an array of problems in the form of increased rates of bone loss and cardiovascular disease. And they also risk experiencing cognitive decline, which tend to be widely overlooked. A 2009 study known as Charter found that a little more than half of all people living with HIV experience some form of cognitive impairment. But not everybody empathize with these problems, even among scientists.

“There’s no doubt that some drugs have side effects and we still don’t know the long term potential headaches they can cause”, says Robert Gallo, director of the Institute of Human Virology and co-discoverer of the HIV virus. “But what I see is pretty much people being able to live a reasonably normal life. In other words, I see it as more of a victory right now than of a chronic low grade defeat”. It might seem a luxury to complain about the consequences of aging with HIV, when, for the first years of the plague, survival itself was at stake. Back then, life expectancy after a positive test was eighteen months. But for people living with the virus these complications represent major challenges.

The increasing cost for treating HIV infections in the US is also of great concern. The average amount spent on each patient is difficult to calculate. Estimates can vary greatly, depending on severity of illness. But, as a study published in the AIDS Journal points out, “the annual per-person costs of care for HIV-infected patients in the United States are high (and) given the potential increases in costs of therapeutic agents, toxicities due to ARVs and aging-related comorbidities, it is likely that the aggregate costs of HIV care will continue to increase for the foreseeable future.” This is bad news for an already cashstrapped health system because it means that, at some point, even an epidemic that remains stable becomes too expensive to afford.

STORIES

SILENCE = DEATH ACT UP, fight back, fight AIDS!

The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) was founded in March 1987 as an organization devoted to direct action – demonstrations and civil disobedience – to call the attention of government officials, scientists, drug companies and the general public to the severity of the AIDS crisis and its impact on the lives of individuals. It was after playwright and author Larry Kramer’s well-attended speech at the Lesbian and Gay Community Center in New York City, focused on action to fight AIDS and the Gay Men's Health Crisis (GMHC) political impotence, that some 300 people met to form ACT UP.

On March 24, 1987, 250 ACT UP members held a demonstration in Wall Street to demand greater access to experimental AIDS drugs and for a coordinated national policy to fight the disease. Seventeen ACT UP members were arrested. A year later, celebrating the first anniversary of the first ACT UP demonstration, the coalition returned to Wall Street but this time more than one hundred activists were arrested. From then on, during the late 1980s and early 1990s, ACT UP New York staged many successful theatrical-innature actions, which captured media attention and brought focus to its messages. Ultimately, ACT UP forced the government to shorten the drug testing and approval process; increase funding for AIDS research, care, and education and promoted legislation to protect the right of HIV+ individuals.

Organized as a leaderless and effectively anarchist network, much of ACT UP's work from 1987 to 1995 was done in committees and working groups devoted to particular topics. The Coalition never registered as a not for profit because it didn’t want anything to do with the government. This kind of uncompromising ethos characterized the group in its early stages but eventually led to a split between those who wanted to remain wholly independent and those who saw opportunities by becoming part of the institutions and systems they were fighting against. Housing Works, New York's largest AIDS service organization, the Treatment Action Group and Health GAP, which fights to expand treatment for people with AIDS throughout the world, are direct outgrowths of ACT UP.

In recent years, with the changing nature and perception of the AIDS crisis, ACT UP's membership has dwindled, even though the 30th anniversary of the epidemic has definitely revived the traditional Coalition’s Monday meetings and brought along a resurgence of AIDS activism. An always increasing number of ACT UP’s first timers, today in their 50s and 60s, are now back on the scene to face, in a country where the transmission rate hasn’t declined but that has managed to turn AIDS into a chronic disease, the new great challenge of aging with HIV.

INFOGRAPHICS USA - Aging

The infographics are presented for informational purposes only. Every attempt has been made to ensure that the information contained herein is accurate. Figures and percentages are based on latest available data as collected by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and published on their respective websites.

THUMBNAILS AND CAPTIONS

A Manhattan view. After the first cases of AIDS reported on the west

coast, New York City quickly became the epicenter of the epidemic in the U.S. Today,

new HIV diagnoses are concentrated primarily in large U.S. metropolitan areas – 81% in

2011 – with New York, Los Angeles, Miami and Washington D.C. topping the list. thirty

years, even though the Federal government’s investment in treatment and research is

helping people with HIV/AIDS to live longer and more productive lives, HIV continues to

spread at a staggering national rate and, by 2015, more than half of all the people living

with HIV/AIDS will be over 50.

A Manhattan view. After the first cases of AIDS reported on the west

coast, New York City quickly became the epicenter of the epidemic in the U.S. Today,

new HIV diagnoses are concentrated primarily in large U.S. metropolitan areas – 81% in

2011 – with New York, Los Angeles, Miami and Washington D.C. topping the list. thirty

years, even though the Federal government’s investment in treatment and research is

helping people with HIV/AIDS to live longer and more productive lives, HIV continues to

spread at a staggering national rate and, by 2015, more than half of all the people living

with HIV/AIDS will be over 50. A Red Ribbon pin on an AIDS advocate suit during the 2013 Positive

Leadership Award Reception at the Capitol Building in Washington D.C. The Awards are

recognized to people who stood up in the fight against AIDS and are held at the end of

AIDS Watch, an annual conference intended to help AIDS advocates to increase

Congressional support for domestic HIV/AIDS appropriations, to educate the Members of

Congress on the importance of implementing and funding health care reforms, and to

urge Congress to repeal criminal laws targeting people living with HIV/AIDS.

A Red Ribbon pin on an AIDS advocate suit during the 2013 Positive

Leadership Award Reception at the Capitol Building in Washington D.C. The Awards are

recognized to people who stood up in the fight against AIDS and are held at the end of

AIDS Watch, an annual conference intended to help AIDS advocates to increase

Congressional support for domestic HIV/AIDS appropriations, to educate the Members of

Congress on the importance of implementing and funding health care reforms, and to

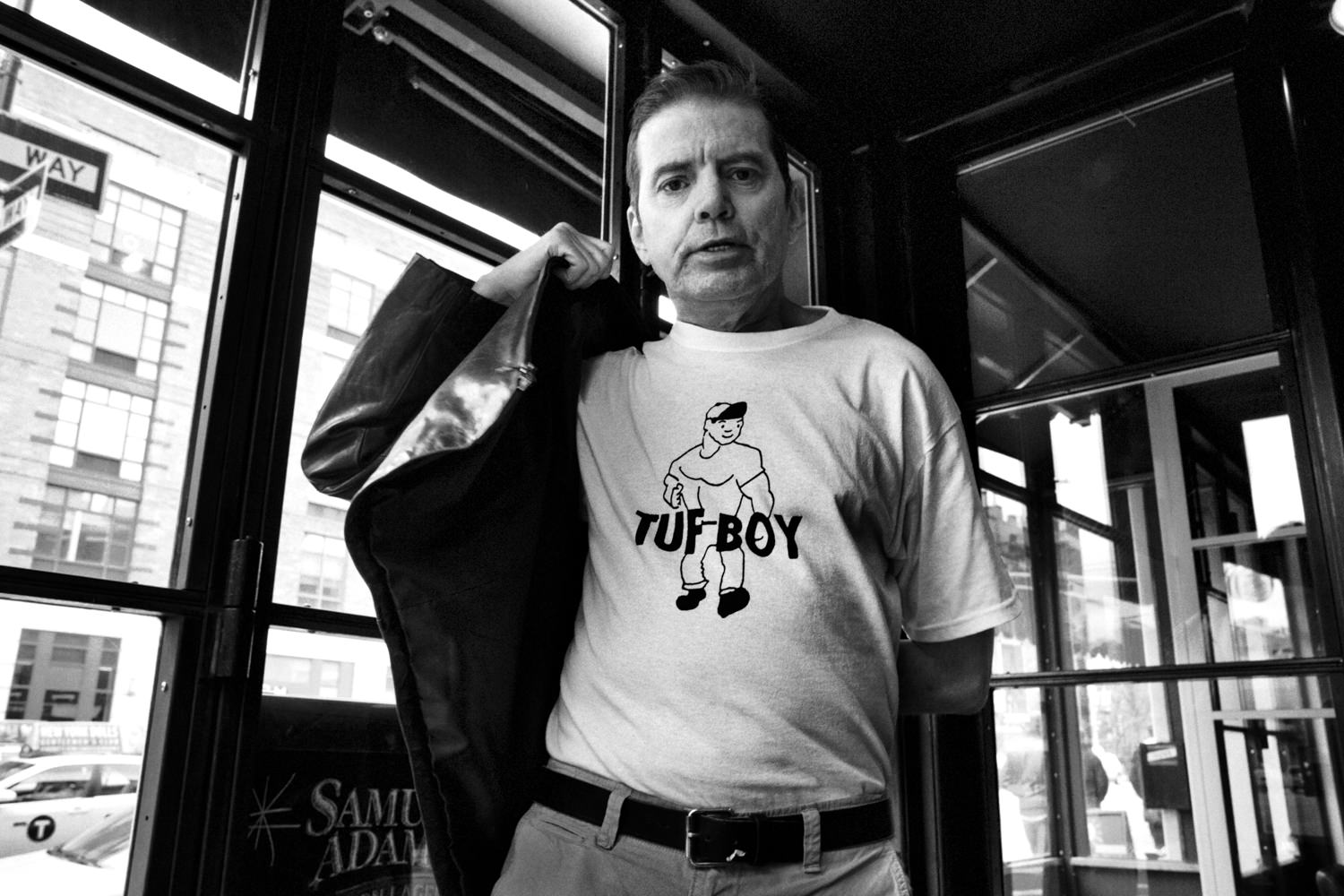

urge Congress to repeal criminal laws targeting people living with HIV/AIDS. Emerging from a Manhattan subway stop. After the first cases of

AIDS reported on the west coast, New York City quickly became the epicenter of the

epidemic in the U.S. HIV incidence and prevalence rates in big cities are the highest in the

country and are strictly connected with high rates of poverty among the most vulnerable

populations. In the United States, since the beginning of the epidemic, over 630,000

people have died of AIDS-related causes, a number greater than the U.S. deaths in the

wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam, Korea and World War II added together.

Emerging from a Manhattan subway stop. After the first cases of

AIDS reported on the west coast, New York City quickly became the epicenter of the

epidemic in the U.S. HIV incidence and prevalence rates in big cities are the highest in the

country and are strictly connected with high rates of poverty among the most vulnerable

populations. In the United States, since the beginning of the epidemic, over 630,000

people have died of AIDS-related causes, a number greater than the U.S. deaths in the

wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam, Korea and World War II added together. Pearl is seen while performing the play “In your face” at the Housing

Works Bookstore, the biggest NYC non profit organization that focuses on stable housing

as a key factor to help HIV+ people live healthy and fulfilling lives. Pearl is part of the 13

Theatre Troupe, an ensemble of NYC artists living with or affected by HIV, that’s been

investigating, based on the real-life experiences of the performers, discrimination towards

homeless and HIV+ New Yorkers since 2011.

Pearl is seen while performing the play “In your face” at the Housing

Works Bookstore, the biggest NYC non profit organization that focuses on stable housing

as a key factor to help HIV+ people live healthy and fulfilling lives. Pearl is part of the 13

Theatre Troupe, an ensemble of NYC artists living with or affected by HIV, that’s been

investigating, based on the real-life experiences of the performers, discrimination towards

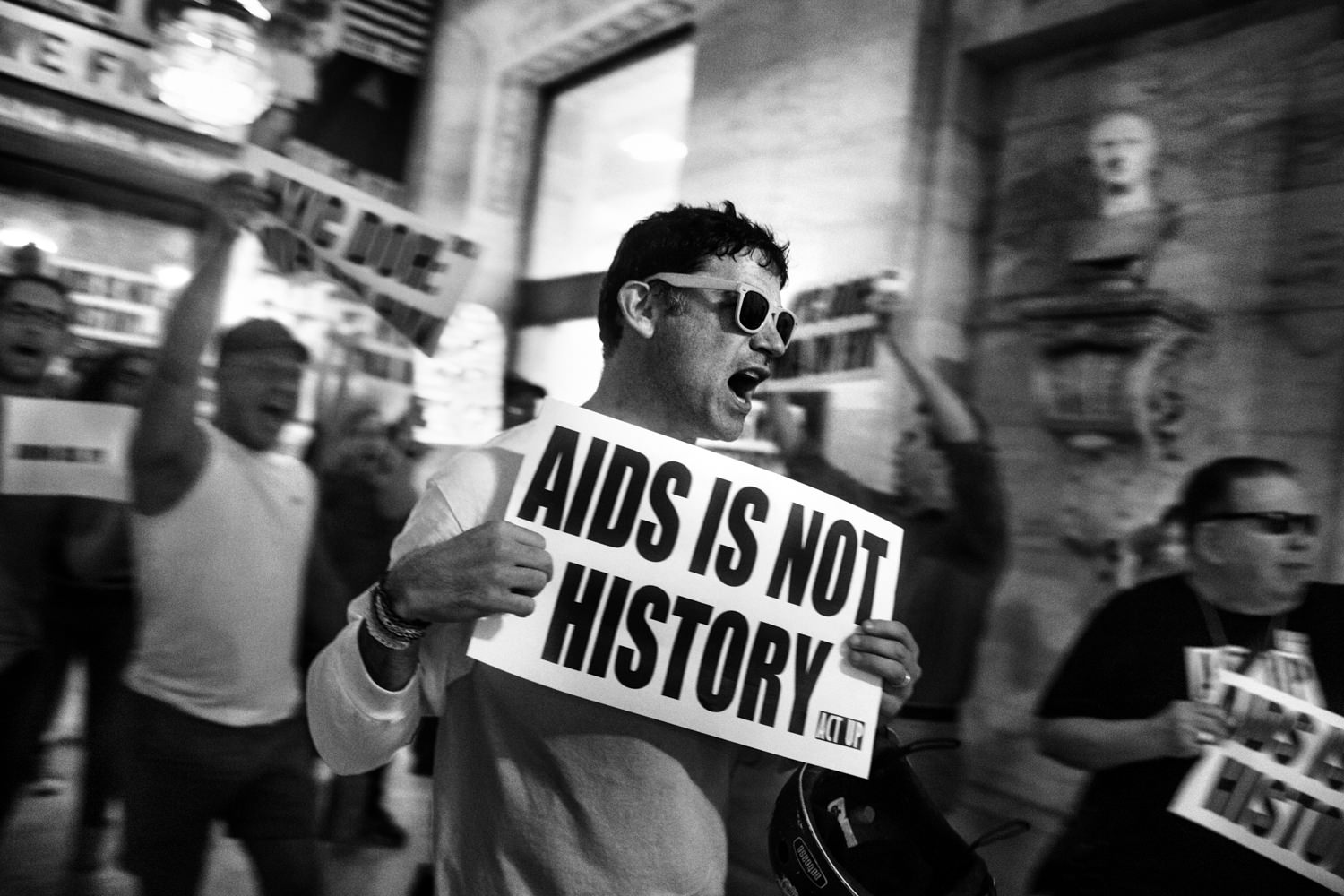

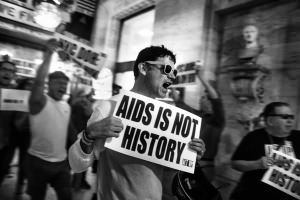

homeless and HIV+ New Yorkers since 2011. Members of ACT UP demonstrate to remember that AIDS is not yet

over at the New York Public Library in occasion of the exhibition “Why We Fight:

Remembering AIDS Activism”. The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) was

founded in March 1987 as an organization devoted to direct action to call the attention of

government officials, scientists, drug companies and the general public to the severity of

the AIDS crisis and its impact on the lives of individuals. The changing nature and

perception of the AIDS crisis in the US has definitely brought to a resurgence of AIDS

activism.

Members of ACT UP demonstrate to remember that AIDS is not yet

over at the New York Public Library in occasion of the exhibition “Why We Fight:

Remembering AIDS Activism”. The AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) was

founded in March 1987 as an organization devoted to direct action to call the attention of

government officials, scientists, drug companies and the general public to the severity of

the AIDS crisis and its impact on the lives of individuals. The changing nature and

perception of the AIDS crisis in the US has definitely brought to a resurgence of AIDS

activism. Diamond, 19, is putting on make up in New Alternatives’ backyard.

New Alternatives is a drop-in center founded in 2008 to increase the self-sufficiency of

homeless LGBT youth. In the United States, for transgender women the risk of infection

with HIV is 36 times higher risk of contracting HIV than a man and an astonishing 78

times higher risk than other women. In 2010, only 3.3% of the CDC’s discretionary AIDS

budget went to prevention and care programs for gay men and transgender women,

although these groups account for nearly two-thirds of new infections.

Diamond, 19, is putting on make up in New Alternatives’ backyard.

New Alternatives is a drop-in center founded in 2008 to increase the self-sufficiency of

homeless LGBT youth. In the United States, for transgender women the risk of infection

with HIV is 36 times higher risk of contracting HIV than a man and an astonishing 78

times higher risk than other women. In 2010, only 3.3% of the CDC’s discretionary AIDS

budget went to prevention and care programs for gay men and transgender women,

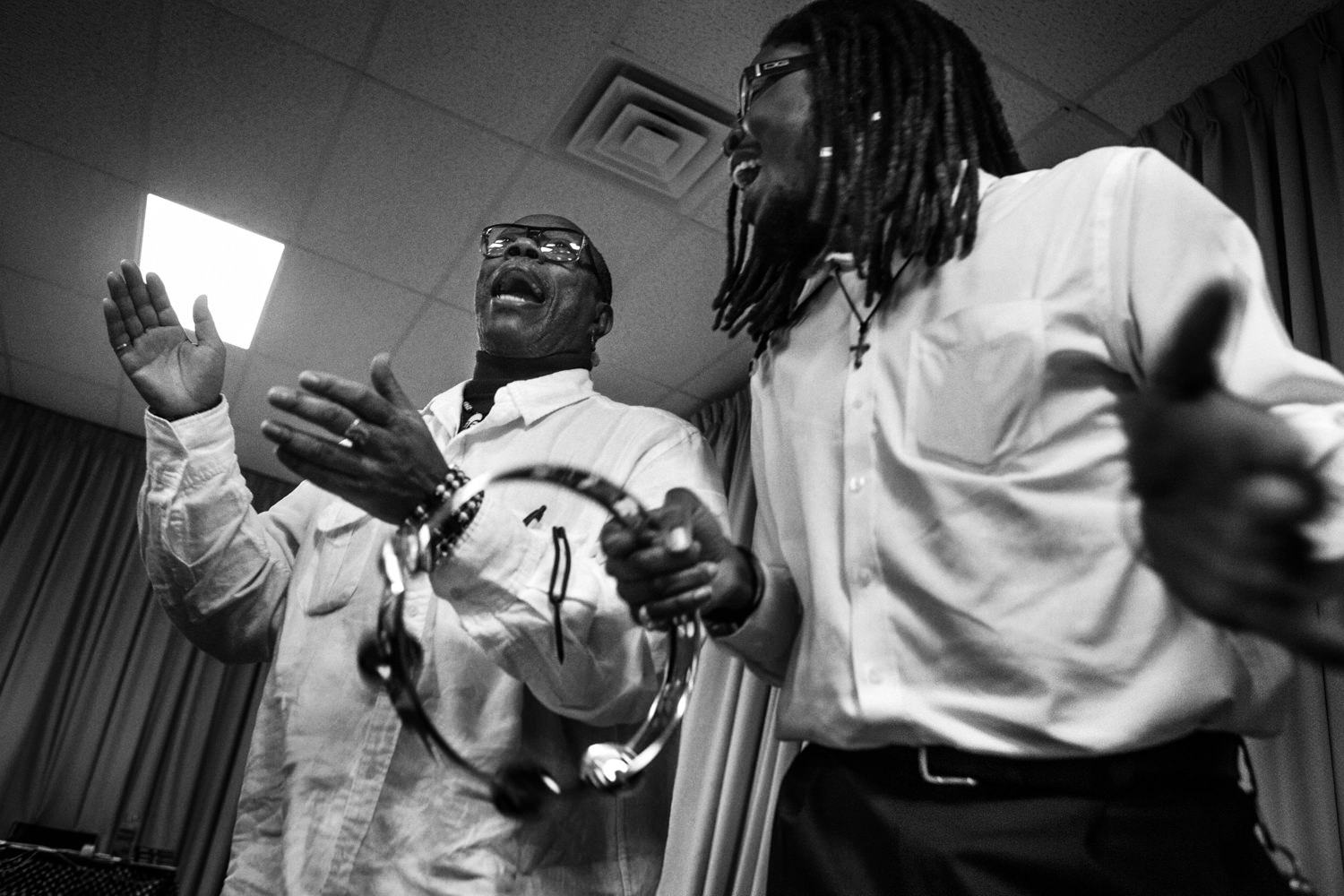

although these groups account for nearly two-thirds of new infections. Reginald T. Brown is a 61 years old HIV+ activist. He’s been living

with HIV since 1986. “I shouldn’t be here for all the unsafe things I’ve done” he says. He

started taking meds only when the anti-retroviral cocktail was first introduced in 1996.

He’s seen while dancing during the Sunday Mass at the Unity Fellowship Church, which

he has joined because of its non-discriminating attitude towards HIV+ people. During the

Mass Reginald has the chance to speak to the public of the Church about the ongoing

AIDS crisis.

Reginald T. Brown is a 61 years old HIV+ activist. He’s been living

with HIV since 1986. “I shouldn’t be here for all the unsafe things I’ve done” he says. He

started taking meds only when the anti-retroviral cocktail was first introduced in 1996.

He’s seen while dancing during the Sunday Mass at the Unity Fellowship Church, which

he has joined because of its non-discriminating attitude towards HIV+ people. During the

Mass Reginald has the chance to speak to the public of the Church about the ongoing

AIDS crisis. The Out of The Closet Thrift Stores in New York and other U.S. cities

are run by the AIDS Healthcare Foundation and offer free HIV testing and counseling. In

2012, an estimated 18% of people living with HIV didn’t know about their status, raising

to over 50% if considering only young gay men. In the U.S., most young people are

infected through unsafe sex practices. Young adults under 35 accounted for 56% of new

HIV infections in 2010.

The Out of The Closet Thrift Stores in New York and other U.S. cities

are run by the AIDS Healthcare Foundation and offer free HIV testing and counseling. In

2012, an estimated 18% of people living with HIV didn’t know about their status, raising

to over 50% if considering only young gay men. In the U.S., most young people are

infected through unsafe sex practices. Young adults under 35 accounted for 56% of new

HIV infections in 2010. Natashanista, a fantasy name composed by Natasha and fashionista,

is having a conversation with some friends in the backyard of New Alternatives, in

Manhattan. New Alternatives is a drop-in center founded in 2008 to increase the selfsufficiency

of homeless LGBT youth. New Alternatives is based on a low barrier-to-entry

harm reduction model — one where youth can just walk in off the street and be fed, or

clothed, or get practical help and psychological support.

Natashanista, a fantasy name composed by Natasha and fashionista,

is having a conversation with some friends in the backyard of New Alternatives, in

Manhattan. New Alternatives is a drop-in center founded in 2008 to increase the selfsufficiency

of homeless LGBT youth. New Alternatives is based on a low barrier-to-entry

harm reduction model — one where youth can just walk in off the street and be fed, or

clothed, or get practical help and psychological support. Woody Barron, 69, is seen in his room at the Broadway House for

Continuing Care, New Jersey’s only specialized facility for the care and treatment of

people living with HIV and AIDS. New Jersey is ranked as the 5th highest State in the

nation with over 35,000 people who are living with HIV/AIDS. Most of the patients at

Broadway House in Newark are long-term survivors and many of them are former

injecting drug user and/or sex workers with a history of extreme poverty.

Woody Barron, 69, is seen in his room at the Broadway House for

Continuing Care, New Jersey’s only specialized facility for the care and treatment of

people living with HIV and AIDS. New Jersey is ranked as the 5th highest State in the

nation with over 35,000 people who are living with HIV/AIDS. Most of the patients at

Broadway House in Newark are long-term survivors and many of them are former

injecting drug user and/or sex workers with a history of extreme poverty. The new One World Trade Center – Freedom Tower skyline. After the

first cases of AIDS reported on the west coast, New York City quickly became the

epicenter of the epidemic in the U.S. Today, new HIV diagnoses are concentrated

primarily in large U.S. metropolitan areas – 81% in 2011 – with New York, Los Angeles,

Miami and Washington D.C. topping the list. Thirty years, even though the Federal

government’s investment in treatment and research is helping people with HIV/AIDS to

live longer and more productive lives, HIV continues to spread at a staggering national

rate and, by 2015, more than half of all the people living with HIV/AIDS will be over 50.

The new One World Trade Center – Freedom Tower skyline. After the

first cases of AIDS reported on the west coast, New York City quickly became the

epicenter of the epidemic in the U.S. Today, new HIV diagnoses are concentrated

primarily in large U.S. metropolitan areas – 81% in 2011 – with New York, Los Angeles,

Miami and Washington D.C. topping the list. Thirty years, even though the Federal

government’s investment in treatment and research is helping people with HIV/AIDS to

live longer and more productive lives, HIV continues to spread at a staggering national

rate and, by 2015, more than half of all the people living with HIV/AIDS will be over 50. Young activists from the Student Global Aids Campaign and from

Health Gap are demanding leadership on the AIDS funding crises due to sequestration

(budget cuts). The recent wave of AIDS activism was triggered by a combination of both

opportunity and threat: on one side, new evidences emerged to prove that ARVs, by

lowering their viral load of HIV+ people, can significantly reduce the odds of new

transmissions and, on the other, global commitment is wavering in the funding of ARV

programs and revisions to international protocols threaten to lessen the ability to override

patent to make generic ARVs available.

Young activists from the Student Global Aids Campaign and from

Health Gap are demanding leadership on the AIDS funding crises due to sequestration

(budget cuts). The recent wave of AIDS activism was triggered by a combination of both

opportunity and threat: on one side, new evidences emerged to prove that ARVs, by

lowering their viral load of HIV+ people, can significantly reduce the odds of new

transmissions and, on the other, global commitment is wavering in the funding of ARV

programs and revisions to international protocols threaten to lessen the ability to override

patent to make generic ARVs available. Daily life in the streets of New York City. After the first cases of AIDS

reported on the west coast, New York City quickly became the epicenter of the epidemic

in the U.S. HIV incidence and prevalence rates in big cities are the highest in the country

and are strictly connected with high rates of poverty among the most vulnerable

populations. In the United States, since the beginning of the epidemic, over 630,000

people have died of AIDS-related causes, a number greater than the U.S. deaths in the

wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam, Korea and World War II added together.

Daily life in the streets of New York City. After the first cases of AIDS

reported on the west coast, New York City quickly became the epicenter of the epidemic

in the U.S. HIV incidence and prevalence rates in big cities are the highest in the country

and are strictly connected with high rates of poverty among the most vulnerable

populations. In the United States, since the beginning of the epidemic, over 630,000

people have died of AIDS-related causes, a number greater than the U.S. deaths in the

wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam, Korea and World War II added together. Anne Fowkles, a HIV/AIDS prevention advocate and, was diagnosed

with HIV at age 59. Living in Baltimore, widowed at 45, after a few years she met an old

high school mate with whom she later started a relationship. He didn’t disclose his status

and she became positive after having unprotected sex with him. Anne is a member of

OWEL (Older Women Embracing Life), an organized network of senior women that

provides support for women who are living with or have been impacted by HIV/AIDS and

for their families and care providers as well.

Anne Fowkles, a HIV/AIDS prevention advocate and, was diagnosed

with HIV at age 59. Living in Baltimore, widowed at 45, after a few years she met an old

high school mate with whom she later started a relationship. He didn’t disclose his status

and she became positive after having unprotected sex with him. Anne is a member of

OWEL (Older Women Embracing Life), an organized network of senior women that

provides support for women who are living with or have been impacted by HIV/AIDS and

for their families and care providers as well. Mariah is a 28 years old transgender woman and LGBT and AIDS

activist. She started spending her days in the west village when she was 13, right after

her mom passed away because of AIDS-related causes. She had her first surgery in 2009

and completed her gender conversion in 2013. Currently she is working to create a

transgender memorial to remind those who died of hate crimes driven by trans-phobic

behaviors. A U.S. 2011 survey that 60% of the transgender interviewed reported violence

or harassment because of their gender identity; 56% of them had been harassed or

verbally abused while 47% had been assaulted or had had objects thrown at them. More

than 20% of all hate crimes are driven by sexual orientation bias.

Mariah is a 28 years old transgender woman and LGBT and AIDS

activist. She started spending her days in the west village when she was 13, right after

her mom passed away because of AIDS-related causes. She had her first surgery in 2009

and completed her gender conversion in 2013. Currently she is working to create a

transgender memorial to remind those who died of hate crimes driven by trans-phobic

behaviors. A U.S. 2011 survey that 60% of the transgender interviewed reported violence

or harassment because of their gender identity; 56% of them had been harassed or

verbally abused while 47% had been assaulted or had had objects thrown at them. More

than 20% of all hate crimes are driven by sexual orientation bias. A panel of a HIV/AIDS awareness campaign is seen in a subway stop

in Manhattan. After the first cases of AIDS reported on the west coast, New York City

quickly became the epicenter of the epidemic in the U.S. Today, new HIV diagnoses are

concentrated primarily in large U.S. metropolitan areas – 81% in 2011 – with New York,

Los Angeles, Miami and Washington D.C. topping the list. thirty years, even though the

Federal government’s investment in treatment and research is helping people with

HIV/AIDS to live longer and more productive lives, HIV continues to spread at a

staggering national rate and, by 2015, more than half of all the people living with

HIV/AIDS will be over 50.

A panel of a HIV/AIDS awareness campaign is seen in a subway stop

in Manhattan. After the first cases of AIDS reported on the west coast, New York City

quickly became the epicenter of the epidemic in the U.S. Today, new HIV diagnoses are

concentrated primarily in large U.S. metropolitan areas – 81% in 2011 – with New York,

Los Angeles, Miami and Washington D.C. topping the list. thirty years, even though the

Federal government’s investment in treatment and research is helping people with

HIV/AIDS to live longer and more productive lives, HIV continues to spread at a

staggering national rate and, by 2015, more than half of all the people living with

HIV/AIDS will be over 50. An AIDS advocate is seen at the annual AIDSWatch conference in

Washington DC. The conference is organized by the National Association of People with

AIDS (NAPWA), the Treatment Access Expansion Project (TAEP) and AIDS United to help

AIDS advocates to increase Congressional support for domestic HIV/AIDS

appropriations, to educate the Members of Congress on the importance of implementing

and funding health care reforms and to urge Congress to repeal criminal laws targeting

people living with HIV/AIDS and to lift the ban on federal funding for syringe exchange

programs.

An AIDS advocate is seen at the annual AIDSWatch conference in

Washington DC. The conference is organized by the National Association of People with

AIDS (NAPWA), the Treatment Access Expansion Project (TAEP) and AIDS United to help

AIDS advocates to increase Congressional support for domestic HIV/AIDS

appropriations, to educate the Members of Congress on the importance of implementing

and funding health care reforms and to urge Congress to repeal criminal laws targeting

people living with HIV/AIDS and to lift the ban on federal funding for syringe exchange

programs. Jim Eigo, a 62 years old HIV negative gay writer, at a weekly ACT UP

meeting at the LGBT Center in Manhattan. “In the early years of the epidemic, AIDS felt

like a medieval plague. At first we could not understand what was happening, except that

we knew that many of us were getting sick and dying at a faster rate than any epidemic in

US history. Today to most gay men the epidemic probably seems troublesome but under

control. The gay community in the US is very complacent about AIDS”. HIV transmission

for gay men in the US is sharply on the rise: up 12% from 2008 to 2010. For a gay man

the risk of infection with HIV is 30 times higher than the risk of a straight man.

Jim Eigo, a 62 years old HIV negative gay writer, at a weekly ACT UP

meeting at the LGBT Center in Manhattan. “In the early years of the epidemic, AIDS felt

like a medieval plague. At first we could not understand what was happening, except that

we knew that many of us were getting sick and dying at a faster rate than any epidemic in

US history. Today to most gay men the epidemic probably seems troublesome but under

control. The gay community in the US is very complacent about AIDS”. HIV transmission

for gay men in the US is sharply on the rise: up 12% from 2008 to 2010. For a gay man

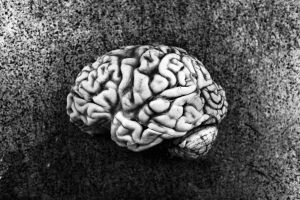

the risk of infection with HIV is 30 times higher than the risk of a straight man. The Manhattan HIV Brain Bank is the largest, multidisciplinary neuro-

AIDS cohort in New York City. The primary research focus is the neurologic,

neuropsychological, psychiatric and neuropathologic manifestations of HIV infection.

Budget sequestration in the U.S. took effect in March 2013 and led to a cut in AIDS

research funding of $153.7 millions, resulting in the loss of funding for an estimated 700

research grants this year. After the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy

(HAART), the U.S. have witnessed a dramatic decrease in mortality rates and increased

life expectancy among people living with HIV/AIDS. With new HIV infection rates

remaining level, the net result is a HIV+ population that is both graying and growing.

The Manhattan HIV Brain Bank is the largest, multidisciplinary neuro-

AIDS cohort in New York City. The primary research focus is the neurologic,

neuropsychological, psychiatric and neuropathologic manifestations of HIV infection.

Budget sequestration in the U.S. took effect in March 2013 and led to a cut in AIDS

research funding of $153.7 millions, resulting in the loss of funding for an estimated 700

research grants this year. After the introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy

(HAART), the U.S. have witnessed a dramatic decrease in mortality rates and increased

life expectancy among people living with HIV/AIDS. With new HIV infection rates

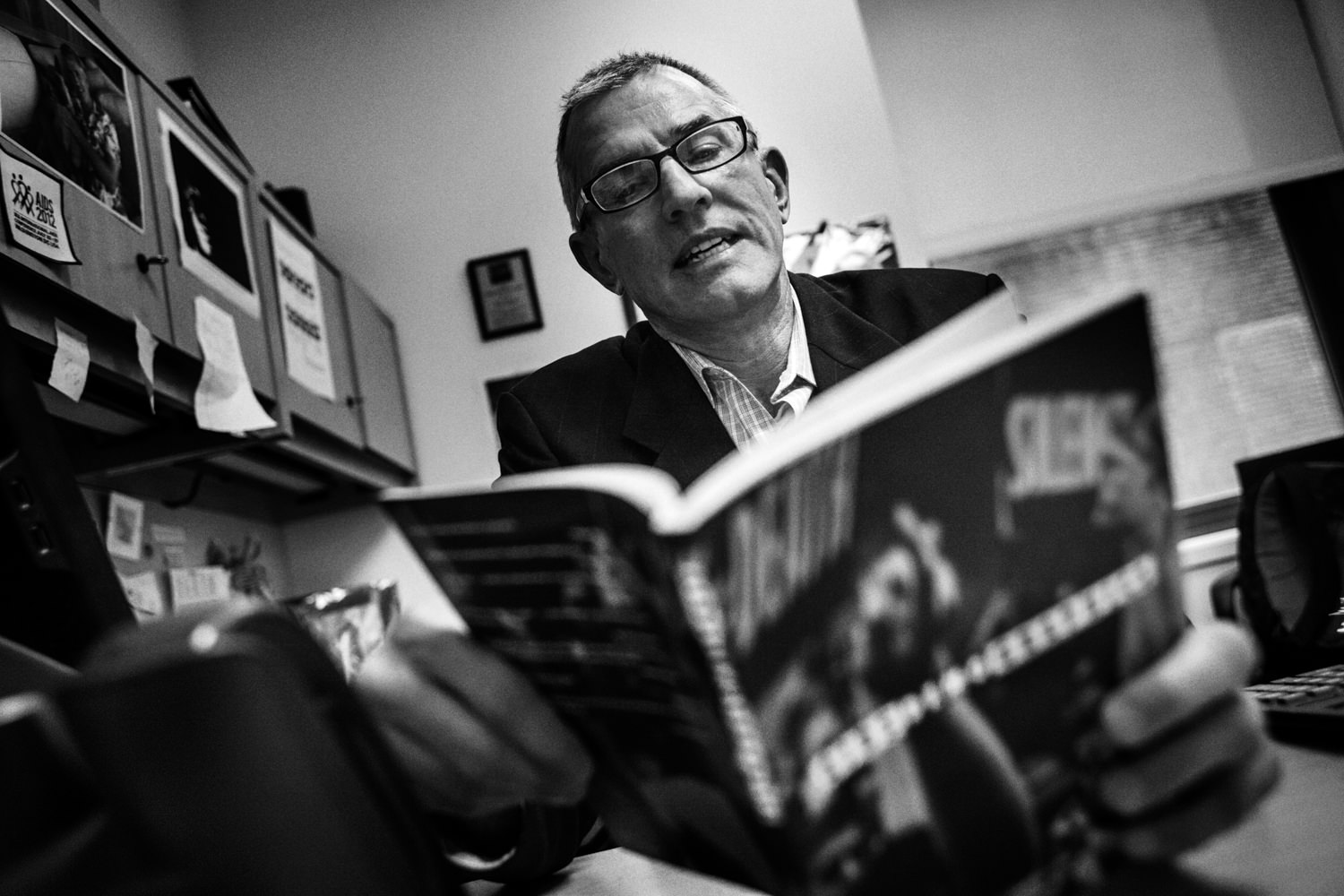

remaining level, the net result is a HIV+ population that is both graying and growing. Gary Morton, 55, is seen while reading and collecting newspapers

articles in his room at the Broadway House for Continuing Care, New Jersey’s only

specialized facility for the care and treatment of people living with HIV and AIDS. New

Jersey is ranked as the 5th highest State in the nation with over 35,000 people who are

living with HIV/AIDS. The House provides services of all kinds and long-term care to its

patients: over 65% of them are usually able to return back into their communities to live

again independently.

Gary Morton, 55, is seen while reading and collecting newspapers

articles in his room at the Broadway House for Continuing Care, New Jersey’s only

specialized facility for the care and treatment of people living with HIV and AIDS. New

Jersey is ranked as the 5th highest State in the nation with over 35,000 people who are

living with HIV/AIDS. The House provides services of all kinds and long-term care to its

patients: over 65% of them are usually able to return back into their communities to live

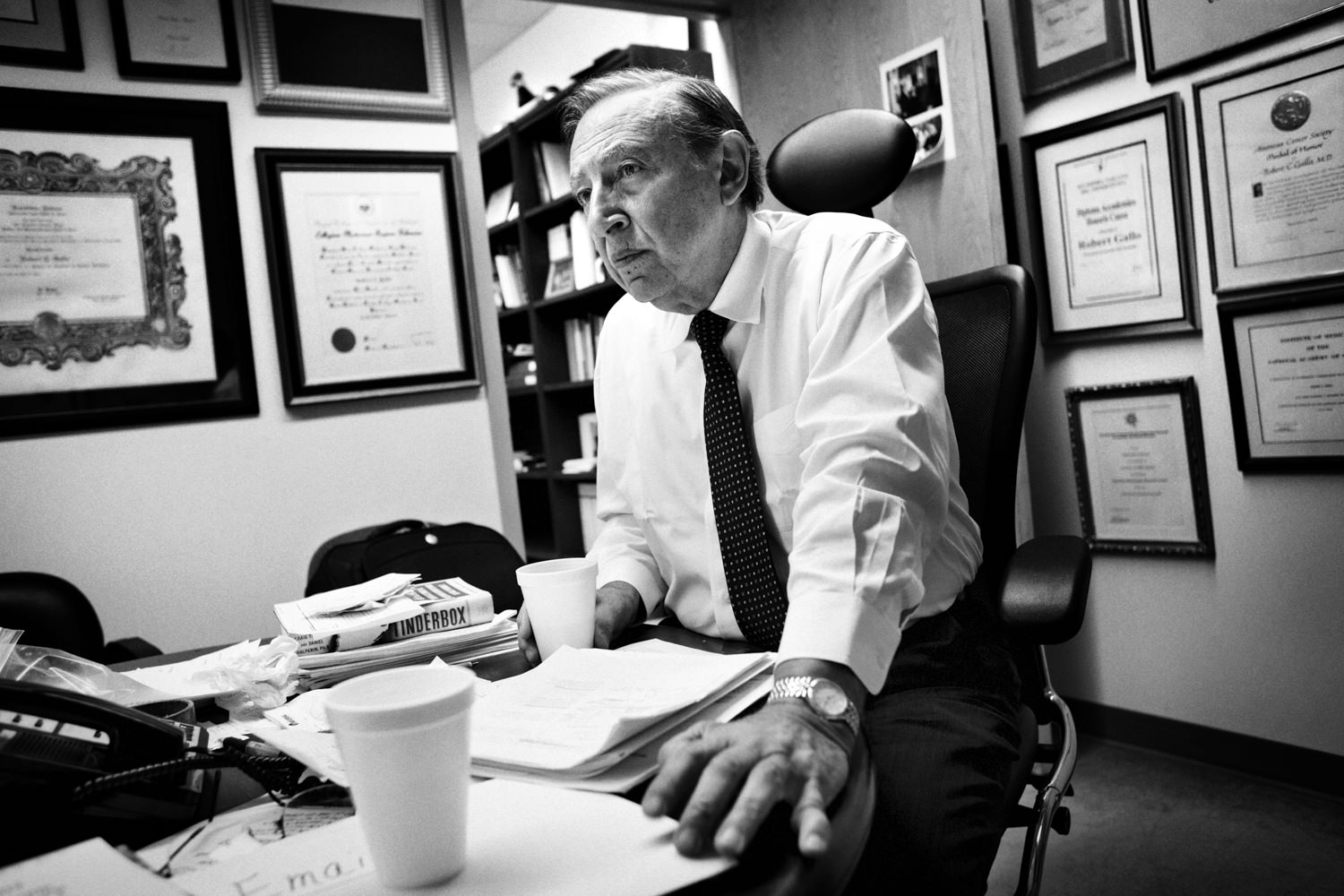

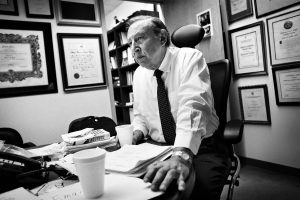

again independently. Dr. Robert Gallo, 76, is an American biomedical researcher best

known for his role in the co-discovery of HIV, the infectious agent responsible for the

acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). He has been a major contributor to

subsequent HIV research and founded in 1996 the Institute of Human Virology at the

University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore. After thirty years he still insists

that HIV testing is the most important tool to keep the epidemic under control.

Dr. Robert Gallo, 76, is an American biomedical researcher best

known for his role in the co-discovery of HIV, the infectious agent responsible for the

acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). He has been a major contributor to

subsequent HIV research and founded in 1996 the Institute of Human Virology at the

University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore. After thirty years he still insists

that HIV testing is the most important tool to keep the epidemic under control. A young transgender is tidying some shelves full of free-to-take

clothes in the offices of New Alternatives, in Manhattan. New Alternatives is a drop-in

center for LGBT Homeless Youth founded in 2008 to increase their self-sufficiency. New

Alternatives is based on a low barrier-to-entry harm reduction model — one where youth

can just walk in off the street and be fed, or clothed, or get practical help and

psychological support. In the United States, for a gay man the risk of infection with HIV is

30 times higher the risk of a straight man while transgender women faces a 36 times

higher risk of contracting HIV than a man and an astonishing 78 times higher risk than

other women.

A young transgender is tidying some shelves full of free-to-take

clothes in the offices of New Alternatives, in Manhattan. New Alternatives is a drop-in

center for LGBT Homeless Youth founded in 2008 to increase their self-sufficiency. New

Alternatives is based on a low barrier-to-entry harm reduction model — one where youth

can just walk in off the street and be fed, or clothed, or get practical help and

psychological support. In the United States, for a gay man the risk of infection with HIV is

30 times higher the risk of a straight man while transgender women faces a 36 times

higher risk of contracting HIV than a man and an astonishing 78 times higher risk than

other women. Valida Henry, 65, has been living at The Bailey-Holt House for the last

seven years. Valida’s legally blind and has had over the years ten strokes. She

seroconverted almost 13 years ago after sharing a syringe with a HIV+ fellow injecting

drugs user. She says she did it “on purpose” because she was willing to commit suicide

and thought that after getting HIV+ she would have died of full blown AIDS soon after.

Valida Henry, 65, has been living at The Bailey-Holt House for the last

seven years. Valida’s legally blind and has had over the years ten strokes. She

seroconverted almost 13 years ago after sharing a syringe with a HIV+ fellow injecting

drugs user. She says she did it “on purpose” because she was willing to commit suicide

and thought that after getting HIV+ she would have died of full blown AIDS soon after. The Baruch Houses, the largest NYC Housing Authority development

in Manhattan. Housing Works, a direct outgrowth of ACT UP, since 1990 has provided

housing and supportive health services to more than 25,000 homeless and low-income

New Yorkers living with HIV/AIDS. After thirty years, even though the Federal

government’s investment in treatment and research is helping people with HIV/AIDS to

live longer and more productive lives, HIV continues to spread at a stable national rate. In

the United States, by 2015, more than half of all the people living with HIV/AIDS will be

over 50.

The Baruch Houses, the largest NYC Housing Authority development

in Manhattan. Housing Works, a direct outgrowth of ACT UP, since 1990 has provided

housing and supportive health services to more than 25,000 homeless and low-income

New Yorkers living with HIV/AIDS. After thirty years, even though the Federal

government’s investment in treatment and research is helping people with HIV/AIDS to

live longer and more productive lives, HIV continues to spread at a stable national rate. In

the United States, by 2015, more than half of all the people living with HIV/AIDS will be

over 50. Two LGBT young homeless are sleeping in the main room of New

Alternatives. New Alternatives is a drop-in center for LGBT Homeless Youth founded in

2008 to increase their self-sufficiency and to enable them to go beyond the shelter

system and transition into stable adult lives. New Alternatives is based on a low barrierto-

entry harm reduction model — one where youth can just walk in off the street and be

fed, or clothed, or get practical help and psychological support. In the United States, for a

gay man the risk of infection with HIV is 30 times higher the risk of a straight man while

transgender women faces a 78 times higher risk than other women. MSM and

transgender people account for nearly two-thirds of new infections.

Two LGBT young homeless are sleeping in the main room of New

Alternatives. New Alternatives is a drop-in center for LGBT Homeless Youth founded in

2008 to increase their self-sufficiency and to enable them to go beyond the shelter

system and transition into stable adult lives. New Alternatives is based on a low barrierto-

entry harm reduction model — one where youth can just walk in off the street and be

fed, or clothed, or get practical help and psychological support. In the United States, for a

gay man the risk of infection with HIV is 30 times higher the risk of a straight man while

transgender women faces a 78 times higher risk than other women. MSM and

transgender people account for nearly two-thirds of new infections. Manhattan as seen from Roosevelt Island. After the first cases of

AIDS reported on the west coast, New York City quickly became the epicenter of the

epidemic in the U.S. HIV incidence and prevalence rates in big cities are the highest in the

country and are strictly connected with high rates of poverty among the most vulnerable

populations. In the United States, since the beginning of the epidemic, over 630,000

people have died of AIDS-related causes, a number greater than the U.S. deaths in the

wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam, Korea and World War II added together. Despite

Federal government’s investment in treatment and HIV continues to spread at a stable

national rate and, by 2015, more than half of all the people living with HIV/AIDS will be

over 50.

Manhattan as seen from Roosevelt Island. After the first cases of

AIDS reported on the west coast, New York City quickly became the epicenter of the

epidemic in the U.S. HIV incidence and prevalence rates in big cities are the highest in the

country and are strictly connected with high rates of poverty among the most vulnerable

populations. In the United States, since the beginning of the epidemic, over 630,000

people have died of AIDS-related causes, a number greater than the U.S. deaths in the

wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam, Korea and World War II added together. Despite

Federal government’s investment in treatment and HIV continues to spread at a stable

national rate and, by 2015, more than half of all the people living with HIV/AIDS will be

over 50.